Australia's next submarine fleet is a hot topic, with the Federal Government creating widespread confusion with its decision to embark on a "competitive evaluation process".

What it seems to be is a process in which offerings from submarine manufacturers in Europe will be compared with what’s on offer from Japan.

They won’t be directly evaluated against each other, as would happen in a tender process, and that’s mostly because the two options offer different benefits (and risks).

A Japanese submarine brings strategic benefits with it that the Europeans can’t match, while Australian industry would likely benefit most if the Europeans get up.

Whichever approach the Government takes in replacing the current Collins class submarines, the Australian taxpayer is likely going to face a bill for $20 billion or more, and for that sort of money it’s worth understanding what we’d get in return.

I’ll explain later why I don’t think subs have to be built in Australia (though they certainly could be). But long before we get to industrial questions such as build location, we should talk strategic fundamentals: why we need submarines and how we’ll use them.

In fact, the rationale for a capable future submarine is a strong one.

Australia has long been the beneficiary of a global economic and security system underpinned in no small way by the dominance of western sea power — mostly provided by the United States US Navy.

Up until the turn of this century, our part of the world was an Asia in which the only significant local powers were US allies: Japan, South Korea and Australia. American sea power could be deployed at will across the western Pacific, as it was during the Taiwan Strait crisis of 1996.

Since then, China has put a lot of effort into building up its ability to deny the seas near its coastline to external forces. A formidable array of cruise and ballistic missiles, sea mines and an increasingly sizeable submarine fleet raise the stakes for any would-be adversary. We mightn’t yet be at the point where an American carrier group can’t safely approach China, but that will be the case sooner rather than later.

And those same technologies are slowly proliferating across the Asian region, including into South-East Asia.

Interactive Map - click on a country target to see more information

If we think it’s necessary to be able to project western sea power anywhere in the Pacific region at times of crisis or conflict, we’re going to need to be able to do it in a much less vulnerable way than sailing large surface vessels into harm’s way.

Australia has a stake in an enduring western naval presence in our region, so a capable submarine presence is important. But, regardless of what we do, the lion’s share of allied submarines in north-east Asia will be American and Japanese.

We’re a long way away from the more contested parts of the western Pacific, and even with 12 subs we couldn’t hope to continuously deploy more than one or two into north Asian waters.

But Australian submarines could be part of a wider Allied strategy, perhaps in a burden sharing arrangement that frees up American submarines.

And an important part of the argument is that America is more likely to remain deeply engaged in Asia if it has allies willing to shoulder part of the cost and difficulty of contesting naval superiority in the region. Australia and Japan working together would play into that picture as well. Of course, having our own submarines would also give us a sovereign capability, and allow us to operate them independently of American forces as well as with them.

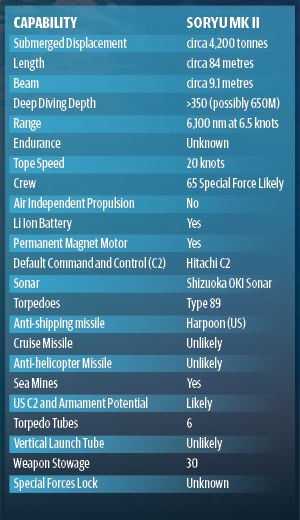

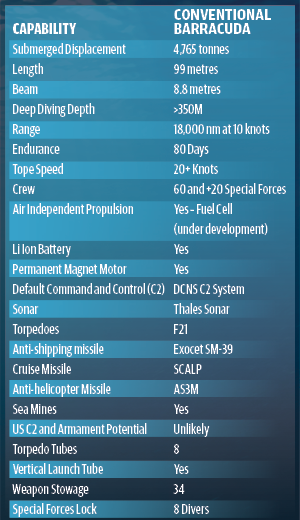

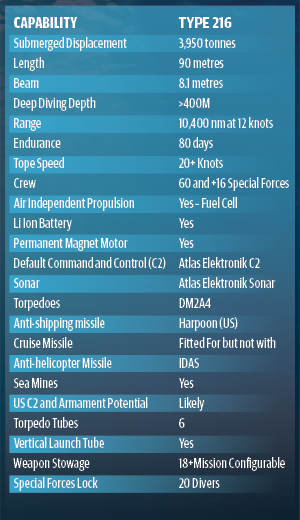

We also have to work out how to get subs. No one builds the large, high-endurance conventionally-powered boat we want, so we’re necessarily going to be looking for a partner to help us modify an existing design, or produce a new one to suit. The consensus now seems to be that the latter course is too risky (and might take too long). So we’re in the market for a submarine designer — and perhaps builder — to help.

In practice, that means we need to work with either Europeans (France or Germany, since Sweden was dropped) or Japan; nobody else really fits the bill.

The Japanese alternative seems to have the inside running, not least because it fits into the Pacific alliance framework described above. As well as being a well-established builder of submarines, involving another US ally would help further cement alliance relationships, especially if we put American weapons and other systems into Japanese hulls.

This brings us to the vexed question — especially for South Australians — of where the boats will be built. One of the last things David Johnston did as Defence Minister was to announce the government’s intention to develop an Australian “sovereign submarine capability”. That was interpreted by some as implying a local build, but that isn’t necessarily the case.

A sovereign capability simply means having the ability to safely and effectively operate submarines. The RAN successfully did that with British-built Oberon submarines during the Cold War, as well as performing a substantial upgrade in Australia. Conversely, for much of its first decade the Adelaide-built Collins class didn’t offer the navy much in the way of capability at all.

It’s over a decade since ASC launched the final new-build Collins, but it’s only now becoming a reliable maintainer of that fleet. It seems that the build location isn’t as critical as the support and management arrangements put in place.

Finally, there are arguments for building here based on local industry and economic benefits.

Those are complex issues — much more so than some public discussion suggests — and I’m sure the government is looking hard at them. In a nutshell, the European countries will probably pitch a build almost entirely here in Australia, and the Japanese probably won’t, though they’re said to be willing to share work with ASC.

But it’s a balance between the total cost, the project risk and the strategic benefits that would follow from the Japanese option, so an offshore build remains a definite possibility. But ultimately support will always be done locally — it simply wouldn’t work any other way — and that’s what we have to get right.